A sculpted indigenous garden featuring more than 60 works by Dylan Lewis.

Explore The Garden

Unearth the wilderness within

Video

Christie’s: Studio Visit

‘Shapeshifting’, an essay by Laura Twiggs

‘Where does animalkind end and humankind begin? What of the wild and the primitive within? In exploring these tantalising enigmas, Lewis searches wilderness, myth and ancient belief systems for inspiration, meaning and answers.’

What’s happening

Featured Events

About the artist

Dylan Lewis Studio

Contact

Tel: +27 (0)21 880 0054

Fax: +27 (0)21 880 0588

Email: info@dylanart.co.za

Stay in Touch

Homage to Löwenmensch

The Löwenmensch (Lion-man) was found in the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave near Munich. Carved from mammoth ivory, the fantastical animal/human hybrid – referred to as a ‘therianthrope’ – stands 31 centimetres tall and features a cave lion’s head and front legs (serving as arms), with a human male torso and legs. While we can only speculate on what the hybrid figure may have meant to those who carved it, the Louwenmensch represents the earliest unequivocal evidence of symbolic thinking in the human archaeological record. This ability set us on a vastly different path from our primate ancestors.

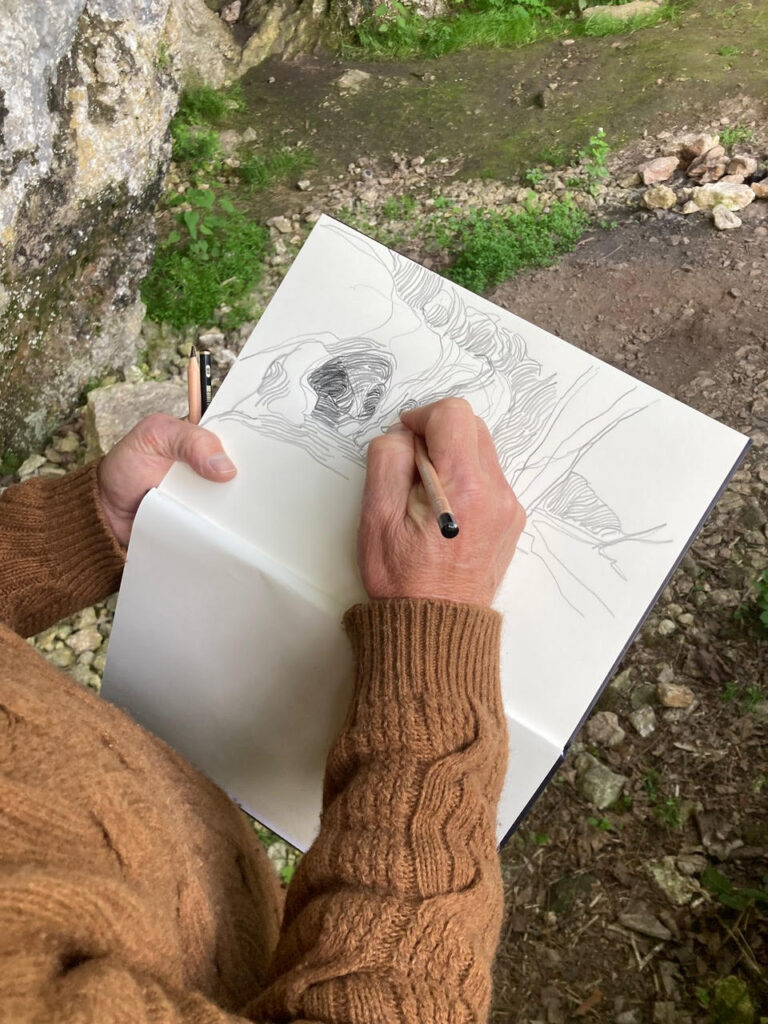

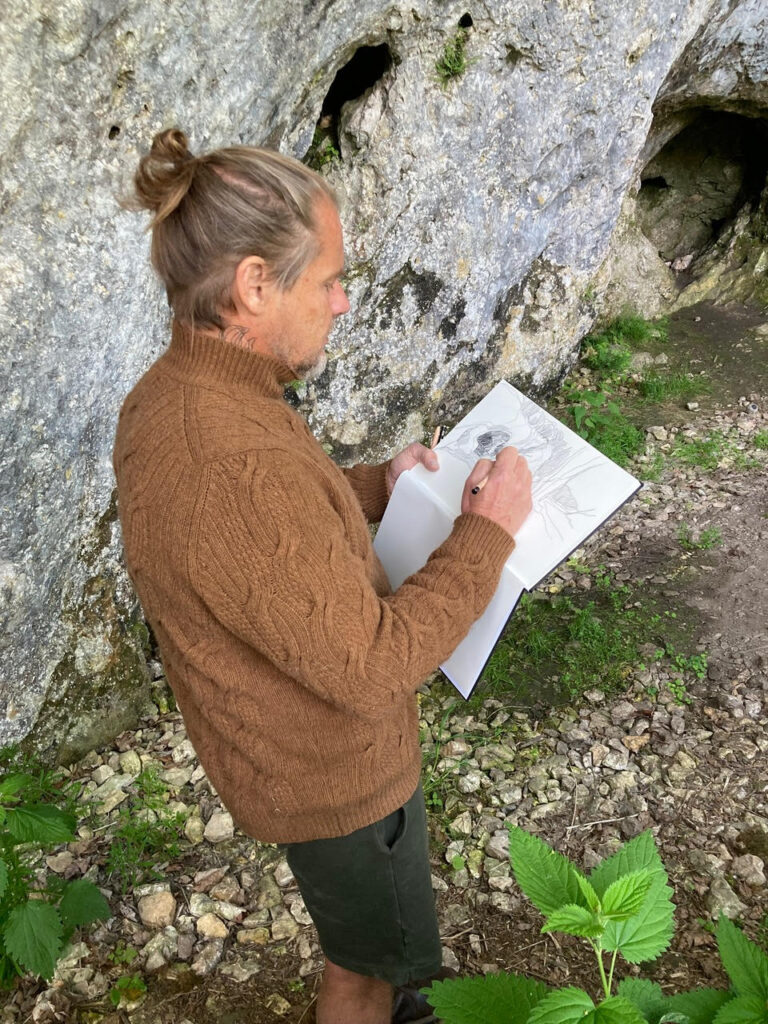

Inspired, Dylan made sketches of the sculpture and visited the cave in which it was found near the Swabian Alb in southern Germany. While reflecting on the 40 000-year span since the figure was carved, he felt acutely aware that this sculpture held meaning for both his own life as well as the trajectory of humankind. Consequently, Dylan produced his sculpture in homage to the Löwenmensch. Similar to its Palaeolithic predecessor, the innermost figure has a human body with a cave lion head. Above it, a human figure wearing a lion skull mask merges into a final figure that is entirely unadorned human.

The lion-headed figure in Dylan’s composition represents the early stages of consciousness as we began to separate from our animal origins. The central shamanistic figure wearing a lion skull mask suggests a time when – although separated from our primal origins – the symbol of the animal remained powerful to hunter-gatherer and early agricultural societies closely attuned to the rhythms of nature. The uppermost figure, fully human, represents the ascent of modern human society. It is striking that this figure’s posture resembles classical depictions of Prometheus, who, in Greek mythology, angered the Gods and endured eternal punishment for gifting fire to humanity. The myth could be interpreted as an allegory for human progress, fire is not just about warmth and light but also represents knowledge, technology, and civilisation. Prometheus’s punishment, therefore, suggests the suffering, alienation and violence which can arise when our pursuit of these advancements relentlessly veers into hubris.

For Dylan Lewis, this juxtaposition points to a fraught dichotomy in the human experience. The sculpture’s circular composition visualises a journey from the emergence of symbolic thinking towards the modern condition. As we strive to embrace technology and progress, Dylan suggests, we find ourselves partially blinded by its brilliance. We are simultaneously pulled back and downward by the weight of the history from which we strove to emancipate ourselves, but are also propelled by it. Yuval Noah Harari puts this well in his book Sapiens when he says “We have Palaeolithic emotions, medieval institutions and godlike technology.”

In an evolutionary timeline, the modern condition is very recent and most of our behaviours and biology were deeply encoded to deal with a very different world. This apparent mismatch could explain many of the seemingly unresolvable paradoxes of the modern human condition. From the artist’s point of view, while it is helpful to attempt to rise above these encoded imperatives it is even more important to understand and come to terms with these forces at play within our individual biology and psyche, as well as the wider social milieu. They are formative parts of ourselves and will not be ignored. It is said that what you don’t let come to you, will come at you.

Photography by Christian Rode and Dylan Lewis

Dylan Lewis Studio

Contact

Tel: +27 (0)21 880 0054

Fax: +27 (0)21 880 0588

Email: info@dylanart.co.za